The discovery and analysis of human remains from the Early Bronze Age site of Charterhouse Warren, located in Somerset, England, has revealed a chilling account of prehistoric violence, shedding light on the brutality and dehumanizing acts that occurred during that period. Archaeologists have examined over 3,000 human bones and bone fragments, concluding that these individuals were victims of a massacre, butchery, and possibly even cannibalism. The evidence paints a grim picture of a society in which violent conflict was not only pervasive but involved acts of extreme violence and dehumanization.

Charterhouse Warren is unique in the archaeological record of Early Bronze Age Britain. While hundreds of human skeletons from this period have been uncovered across the country, direct evidence of violent conflict during this time is relatively rare. More often, injuries associated with violence are found in skeletal remains from earlier periods, such as the Neolithic. However, the Charterhouse Warren site presents a stark exception, revealing a significantly higher level of violence than might have been expected for this era. Professor Rick Schulting, the lead author of the study and an expert from the University of Oxford, notes, “We actually find more evidence for injuries to skeletons dating to the Neolithic period in Britain than the Early Bronze Age, so Charterhouse Warren stands out as something very unusual.”

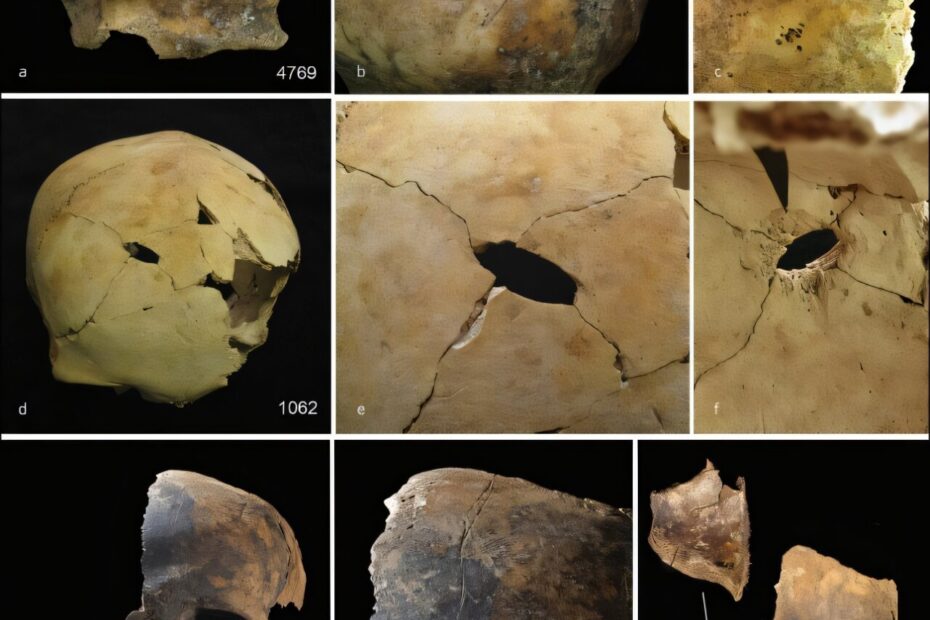

The human remains discovered at Charterhouse Warren were unearthed in the 1970s in a deep shaft, measuring 15 meters in depth. The bones belonged to at least 37 individuals, a mix of men, women, and children, which suggests that the assemblage likely represented an entire community. Unlike most burial sites from this time, the remains from Charterhouse Warren showed clear signs of violent deaths, with skulls exhibiting blunt force trauma that indicated violent, sudden attacks. These discoveries raised many questions about the circumstances surrounding the deaths of these individuals.

To unravel the mystery, researchers from several European institutions conducted a comprehensive analysis of the bones, and their findings were published in the prestigious journal Antiquity. The analysis revealed numerous cut marks and perimortem fractures—injuries inflicted around the time of death—which suggested that the bodies had been intentionally butchered. Additionally, evidence indicated that some of the individuals may have been cannibalized. This raised the question: why would people in Early Bronze Age Britain resort to cannibalism, particularly given the plentiful natural resources available at the time?

The answer, according to researchers, is not likely to be a practical necessity for food. There was a large amount of cattle remains found alongside the human bones, indicating that the people of Charterhouse Warren had ample access to food sources other than human flesh. Rather than a survival strategy, cannibalism in this context appears to have been an act of ritualistic dehumanization. The act of eating the flesh of the deceased and mixing their bones with animal remains likely served to “other” the victims, dehumanizing them by likening them to animals. The perpetrators may have been attempting to eliminate any semblance of humanity from their enemies, rendering them mere objects for consumption and disposal.

This interpretation stands in contrast to findings from other prehistoric sites. At Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Gorge, for example, evidence of cannibalism suggests that it may have been part of a funerary ritual, perhaps connected to ancestor worship or burial practices. However, the situation at Charterhouse Warren is markedly different. Unlike the findings at Gough’s Cave, where there is evidence of ritualistic violence, the deaths at Charterhouse Warren appear to have been the result of an unexpected and sudden attack. The bones show no signs of a struggle, suggesting that the victims were taken by surprise, possibly during a raid or ambush. It is likely that the individuals were massacred by their enemies, and the subsequent butchery of the bodies was a calculated act of violence meant to strip away their humanity.

The reasons behind the violence at Charterhouse Warren remain unclear, but social factors appear to have played a significant role. Researchers have ruled out resource competition or climate change as primary drivers of conflict in Britain during this period. Unlike later periods, there is no evidence to suggest that communities of different ethnic or genetic backgrounds were living in close proximity, making ethnic conflict an unlikely explanation. Instead, the violence may have been triggered by social factors such as theft, personal insults, or long-standing rivalries. In particular, there is evidence that two children from the site had teeth infected with plague, which raises the possibility that disease could have exacerbated social tensions, further fueling conflict.

The discovery of plague-related infections is an unexpected and intriguing aspect of the study. Professor Schulting notes, “The finding of evidence of the plague in previous research by colleagues from The Francis Crick Institute was completely unexpected. We’re still unsure whether, and if so how, this is related to the violence at the site.” It is possible that the presence of disease contributed to the breakdown of social structures, increasing tensions between groups and making violence more likely. However, further research is needed to fully understand the connection between the plague and the massacre at Charterhouse Warren.

The findings at Charterhouse Warren offer a glimpse into the darker side of prehistoric human behavior, illustrating how social tensions, real or perceived, could escalate into extreme acts of violence. Professor Schulting comments, “Charterhouse Warren is one of those rare archaeological sites that challenges the way we think about the past. It is a stark reminder that people in prehistory could match more recent atrocities and shines a light on a dark side of human behavior.” These events at Charterhouse Warren, while extreme, are not entirely unprecedented in human history. Throughout the centuries, cycles of violence, revenge, and retaliation have been driven by similar social dynamics.

The violence uncovered at Charterhouse Warren serves as a reminder that the past was not always peaceful and that human history is replete with acts of cruelty and dehumanization. What is particularly disturbing about this discovery is that it appears unlikely to have been an isolated event. The researchers suggest that the violent massacre at Charterhouse Warren may have been part of a broader pattern of violence, indicating that similar acts could have occurred elsewhere in prehistoric Britain.

The study of Charterhouse Warren thus raises important questions about the nature of prehistoric societies and their ability to engage in extreme violence. While the evidence from this site is rare, it contributes to our understanding of how social factors, including perceived insults, diseases, and rivalries, could lead to massacres and acts of brutality. It challenges the conventional view of Early Bronze Age Britain as a relatively peaceful period and suggests that the people of this time were capable of actions that we might associate with more recent historical events.

Source: Antiquity