Astronomers have long been intrigued by Venus, our closest planetary neighbor, often envisioning it as a world that may have once mirrored the hospitable conditions of Earth. However, recent research led by a team from the University of Cambridge has upended this narrative. Their findings, published in Nature Astronomy, suggest that Venus has likely been a hostile and barren world throughout its entire history, never possessing the conditions necessary to support liquid water or life.

The study’s conclusion arises from a detailed analysis of Venus’s atmospheric chemistry and its volcanic processes. The researchers found that the interior of Venus is too arid to have ever supported the vast quantities of water required to form oceans. This insight challenges decades of speculation and provides critical implications for the search for life elsewhere in the universe.

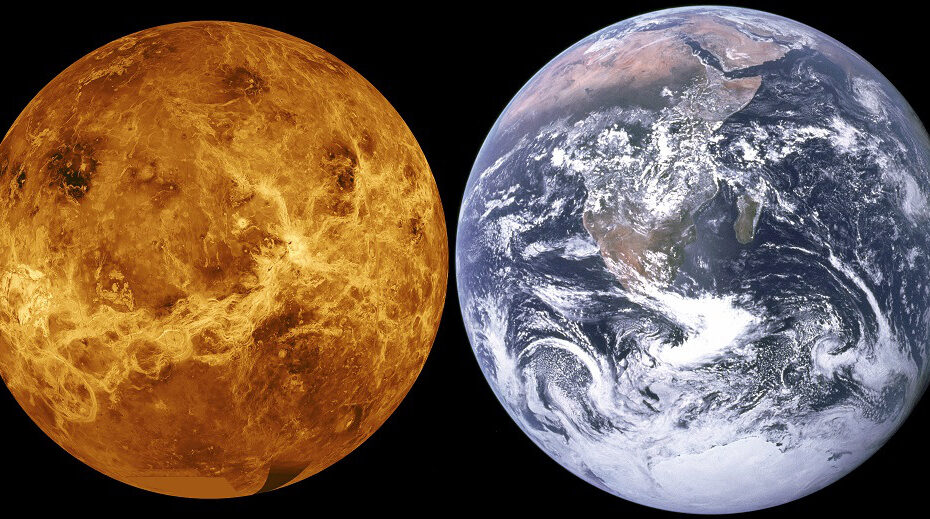

From a distance, Venus appears to share several characteristics with Earth. Its size, mass, and rocky composition make it an almost identical twin to our planet. Yet a closer examination reveals a stark contrast: Venus is shrouded in thick clouds of sulfuric acid, and its surface temperature averages a blistering 500°C—hot enough to melt lead. These conditions make it a world far removed from Earth’s temperate and life-supporting environment.

Despite these extreme differences, the possibility of Venus having once been more Earth-like has long fascinated scientists. Some speculated that its surface might have harbored liquid water in the distant past or that unique forms of aerial microbial life could exist within its dense, acidic clouds today. The notion that Venus may have had a habitable phase fed into broader astronomical studies, as researchers considered its implications for understanding exoplanets—planets beyond our solar system—and the conditions required for life.

Central to the team’s investigation was the chemical composition of Venus’s atmosphere. According to Tereza Constantinou, a Ph.D. student at the University of Cambridge and the study’s lead author, the chemistry of a planet’s atmosphere is deeply interconnected with its interior processes. Volcanism, for instance, plays a critical role in shaping and sustaining atmospheric compositions by releasing gases as magma rises from the mantle to the surface. On Earth, these eruptions are rich in water vapor due to our planet’s water-laden interior. Venus, however, tells a different story.

The researchers calculated the rate at which water and other molecules like carbon dioxide and carbonyl sulfide are destroyed in Venus’s atmosphere. To maintain equilibrium, volcanic gases must replenish these molecules. Their analysis revealed that the volcanic gases sustaining Venus’s atmosphere contain no more than six percent water, indicating a severely dry interior. This scarcity of water suggests that Venus’s mantle—the source of its magma—has been parched since its formation, ruling out the possibility of past oceans.

This finding adds weight to one of the two prevailing theories about Venus’s evolution. The first theory posits that Venus once had temperate conditions, possibly supporting liquid water, but later succumbed to a runaway greenhouse effect caused by rampant volcanic activity. The second theory, now supported by this study, argues that Venus was born with an inherently hot and arid environment, preventing water from ever condensing on its surface.

The implications of this research extend far beyond Venus. For decades, astronomers have focused on the habitable zone around stars—the range of distances where a planet’s surface temperature might allow liquid water to exist. Venus serves as a boundary marker for this zone, highlighting the conditions under which planets lose their potential for habitability. The findings suggest that planets resembling Venus in their proximity to their host stars are less likely to support life.

This insight is particularly relevant to the study of exoplanets, many of which are Venus-like in size, composition, and proximity to their stars. Instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope excel at studying these planets, but the new research advises caution. If Venus has always been uninhabitable, it narrows the scope of potentially life-supporting planets to those that more closely resemble Earth in their atmospheric and geological properties.

The study’s conclusions come at a pivotal time for Venus exploration. NASA’s forthcoming DAVINCI mission, set to launch later this decade, will provide a closer look at Venus through a series of flybys and a descent probe. This mission will analyze the planet’s surface and atmosphere, offering the most detailed data yet on its composition and history. These findings could confirm whether Venus has been an unchanging inferno or if there are nuances to its evolution that remain undiscovered.

While the results of the Cambridge study may disappoint those hoping Venus once had an Earth-like past, they offer valuable guidance for future explorations of life in the cosmos. “If Venus was never habitable,” said Constantinou, “it makes Venus-like planets elsewhere less likely candidates for habitable conditions or life.” The study underscores the importance of refining the criteria astronomers use to identify potentially life-supporting worlds, directing attention toward planets with characteristics more aligned with Earth’s.

The findings also underscore the broader significance of Venus in planetary science. Despite its proximity and similarity to Earth, Venus evolved into an entirely different world, offering a compelling case study in planetary diversity. By understanding what makes Venus so uninhabitable, scientists gain critical insights into the factors that allow Earth to support life. This knowledge not only enhances our appreciation of Earth’s uniqueness but also informs the search for habitable planets in other star systems.

Source: University of Cambridge