Archaeologists Dr. Wim van Neer, Dr. Bea De Cupere, and Dr. Renée Friedman have recently published groundbreaking research in the Journal of Archaeological Science that reveals the earliest physical evidence of livestock horn modification. This discovery, made at the elite burial complex in Hierakonpolis, Upper Egypt, dates back to approximately 3700 BC and represents the first known instance of such modification in sheep. While horn alteration has been previously documented in African cattle through rock art depictions, this study marks a significant addition to our understanding of livestock management and cultural practices in early Egyptian history.

The site of Hierakonpolis, located about 100 kilometers from modern Luxor, was an important center of culture and power during the Predynastic period. The burial complex there contained elaborate tombs for the city’s elite, who were often interred with a variety of wild and exotic animals. These included not only typical livestock such as cattle and goats but also more unusual species like elephants, crocodiles, baboons, hippos, leopards, and hartebeests. Among these animals were sheep, some of which displayed deliberate horn modifications. This practice, as the study reveals, appears to have served both aesthetic and symbolic purposes, underscoring the social and religious significance of these animals in Predynastic Egypt.

The researchers identified the modified sheep remains in tombs 54, 61, and 79, uncovering evidence of six individual sheep whose horns had been intentionally altered. These modifications included complete removal of horns and reshaping them to point backward, parallel, or upwards. Additionally, the examination of skeletal remains revealed that some of these sheep had been castrated, as indicated by their unusually elongated bones and the presence of unfused growth plates. Castration typically results in larger-than-average livestock, further distinguishing these sheep from those bred for everyday consumption.

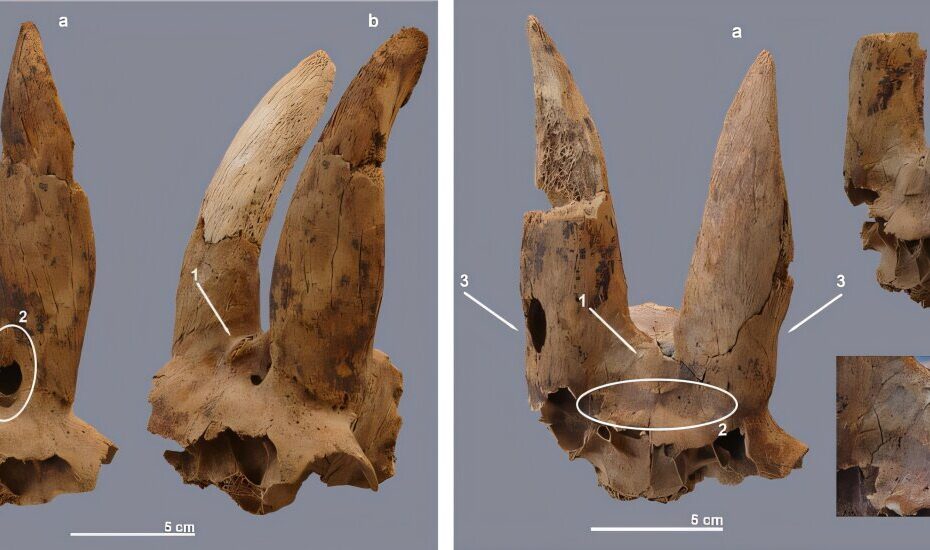

The process of horn modification involved a technique known as fracturing. The skull at the base of the horn core was deliberately fractured, after which the horn was repositioned and secured in place using bindings. The fractures were allowed to heal over a period of weeks, resulting in permanent reshaping of the horns. This conclusion was drawn from the presence of depressions at the base of the horn cores, thin bone structure in the affected areas, and constrictions on the sides of the horn cores consistent with the use of bindings. Such practices are still employed today by agro-pastoralist groups like the Pokot of Kenya, who modify the horns of their goats for cultural and practical reasons when the animals are about a year old.

The significance of these modified sheep extends beyond mere physical alterations. Dr. van Neer notes that these practices were likely a means for the elite to display their power and control, not only through the ownership of exotic animals but also by manipulating the appearance of domestic species. In this way, the sheep became more than livestock—they were symbols of prestige, control, and perhaps even cosmic order. Predynastic Egyptian elites placed a high value on their ability to dominate and manipulate nature, a concept reflected in their procurement and burial of dangerous and wild animals such as hippos, baboons, and elephants. The modified sheep, with their castration and altered horns, represented another way of transforming ordinary animals into extraordinary symbols of elite status.

These sheep may also have held religious or symbolic significance. The researchers suggest that the modified horns could have been designed to evoke the addax, a type of antelope with upright spiral horns. The addax (Addax nasomaculatus) was often associated with themes of renewal and the triumph of order over chaos in Egyptian iconography. Such associations would have imbued the sheep with a deeper meaning, aligning them with the cultural and spiritual ideals of the time. The practice of horn modification, then, was not merely practical or aesthetic but also laden with symbolic and religious significance.

The sheep found at Hierakonpolis were clearly not intended for routine consumption. Their advanced age—ranging from six to eight years—was far beyond the typical lifespan of sheep raised for meat, which are usually slaughtered by age three. Combined with their castration and horn modifications, this suggests these animals were reserved for ceremonial purposes or as markers of social prestige. The burial of these sheep alongside humans in elite tombs further reinforces their importance within the cultural and religious framework of Predynastic Egypt.

The researchers emphasize that this discovery enriches our understanding of early livestock management and the interplay between human societies and their domesticated animals. It provides tangible evidence of how the manipulation of animal forms was used to convey status, power, and religious ideals. The ongoing excavation at Hierakonpolis aims to uncover whether similar practices were applied to other livestock, such as cattle and goats. Dr. van Neer expressed optimism, stating, “We will keep our eyes open for other examples of horn modification at the site of Hierakonpolis; in particular, we want to know whether horn modification was also practiced in cattle and goats.”

The implications of this study extend far beyond the specific context of Hierakonpolis. By demonstrating that horn modification in sheep was practiced as early as 3700 BC, the research sheds light on the sophistication and complexity of Predynastic Egyptian animal husbandry practices. It also highlights the symbolic and cultural roles that livestock played in early societies, providing new perspectives on how humans have historically interacted with and shaped the natural world.

This discovery adds another layer to our understanding of the evolution of human-animal relationships, particularly in a region as historically significant as ancient Egypt. As excavations continue, researchers hope to uncover more evidence that will further illuminate the practices, beliefs, and innovations of early Egyptian civilizations. For now, the modified sheep of Hierakonpolis stand as a testament to the ingenuity and cultural depth of Predynastic Egypt, offering a glimpse into the ways in which its people sought to assert their dominance over both the natural and symbolic realms.